In this inspiring guest post, writer Shelley Dark shares her experience of Hydra, Greece in the off-season, when the island slows down to its own quiet rhythm. I loved how Shelley Dark captures the silence, the drizzle, the warmth of strangers, and the beauty of simply being.

Her reflections made me want to wander Hydra’s cobblestone alleys again (I have been there only once many years ago and loved the vibe), and sip wine by the sea with nowhere else to be. This is Hydra, unfiltered and at peace — and Shelley’s words are a gentle reminder of why I prefer slow travel.

Enjoy – and do look out for Shelley Dark’s books!

Where to stay in Hydra, Greece

Activities to do in Hydra, Greece

How to Get There – Check your Airplane Tickets Here

How to Get There – Book Your Ferry Tickets Here

Hydra Greece Travel Guide by Shelley Dark (c) Brisbane Headshots

Hydra – by Shelley Dark

Hydra in winter is a well-kept secret. The ferry carries mostly locals who’ve been to Athens on business and it empties out onto an empty quay. The port cafés are shuttered or sleepy. No one is shouting and only one or two tourists pull their luggage across the cobblestones. Just the tiered mansions, the donkeys, and the smell of the sea.

It takes a certain kind of person to visit Hydra in the off-season—and a certain kind of luck. You have to enjoy silence and a little drizzle. You have to be able to eat whatever the taverna is serving. You have to find beauty in olive trees and empty lanes and chilly winds.

In return, you’ll be let in on something many visitors never see: what Hydra is like when she’s just being herself.

Morning is for the Senses

I would wake in my rented apartment in a shipowner’s mansion on the port to the clatter of hooves—an early donkey heading into town to collect hay for his dinner. No cars are allowed on Hydra. Not ever. Which means the soundtrack of your life is hoofbeats, the clack of ships’ rigging, and cooing pigeons on the roof.

I liked to sleep in or work at my computer early, while the drizzle came across in curtains, and walk later, when the sun climbed over the hills. I’d pass shops closed ‘for the season,’ stone houses stacked in an amphitheatre, cats sprawled as if they own the place—and they do. If I walked west, I’d end up at Kamini or Vlychos, where the tavernas might still be closed but the grasses were a soft green and wild lilies bloomed.

Once, an old woman called to me on the path. I thought she might need help. Instead, she told me that the Apokries festival was on the next day. “It’s great fun,” she said. “You must come.” I nodded and grinned like a fool. She grinned back. The daily bulletin on Hydra.

Walking Nowhere and Everywhere

Without a schedule, the island becomes a map of possibilities. One day I climbed the steep stone path to the Prophet Elias Monastery. George from next door saw me go and asked me where my umbrella was. A three-hour round trip, and only one other soul in sight—a French tourist. At the top, I had views over the Peloponnese and the tiny town way below. The wind made me glad I was wearing my anorak, and I had the sense that time had slipped sideways.

Another day, I was utterly lost in the backstreets, admiring the age-faded doors. A woman on a high balcony was pulling her groceries up on a rope. She happily stopped to give me full directions—or a comment on my life choices, I still don’t know. I thanked her and found my way down.

There is something sacred about walking just to walk. No timetable. No goal. Just the echo of your own footsteps as you stand aside for the odd donkey.

Because you walk everywhere—up steps, down steps, along flagstones and rough tracks—you deserve your lunch. In the cool winter air, the movement makes you feel lighter, clearer-headed, stronger. That has to be good for your heart, in more ways than one.

Make time for detours. Walk to Mandraki and imagine summer swimmers climbing down the steep stone stairs to the waterline, diving from the concrete aprons, laughter drifting up from the same spots that now lie quiet. Admire the tiny white church perched on the edge of a jack‑knife inlet. See the cannon. Dream of the revolution. Look up at the old windmills and imagine them crushing grain into flour.

And just once, leave your umbrella behind and let the rain hit your face.

Living Small, Breathing Big

Hydra in winter strips life to its bones—in the best way. You don’t need much. A warm coat and a scarf. A good book. A glass of wine. I had two outfits, my laptop, and a little balcony on the sea.

I read. I wrote. I thought thoughts. My brain, which is usually like a browser with 47 tabs open, was quiet. Except for the growing conviction I would write a novel.

Once, I stood at my window overlooking the port for a full hour watching a fisherman and his wife untangle their nets, the sounds of bouzouki music playing a melody from a portable radio. They didn’t notice me. Or if they did, they didn’t mind. That’s winter on Hydra. Nobody’s trying to entertain you. But you’ll find yourself entertained.

And why not indulge a little? Book a massage. Have a facial. Buy a bunch of pink alstroemeria from the florist in the backstreets. Pop into a church and sit for a while—even if the bells are ringing. Don’t rush. The service won’t start for a while.

Half a Day in the Past

I had business at the Historical Archives Museum of Hydra, right on the eastern side of the port in a gracious stone mansion once belonging to a shipowner. It’s a quiet delight.

Inside, you’ll find charming archivists, ship models, navigational instruments, cannons, lithographs, and even nineteenth century traditional Hydriot costumes. Not to mention wood carvings from the prows of 19th‑century vessels, paintings, maps, and oil portraits of serious town fathers which bring the island’s revolutionary past into sharp focus. The silver urn bearing the embalmed heart of Admiral Andreas Miaoulis is among the most revered artifacts.

The archives and library—filled with thousands of manuscripts, rare books, and formal correspondence—reach from the 18th through the early 20th centuries. There are no crowds in winter. No hurry. Just you, the hush of history, and the faint echo of cannon fire from the display cases.

The People Who Stay

I’ve been to Hydra in summer—full of yachties, influencers in linen, lovers, families, tourists, artists, poets. In winter, the artists have time to talk.

In the cafés, I’d see the same few locals every day. The priest, the man with the dog, the woman with her back to the sea. Eventually, they started to nod. Then smile. We’d exchange pleasantries.

Eileen on the corner offered me a piece of her sister’s cake and a tiny glass of limoncello. I swear her waffle and ice cream tasted of kindness.

About the Food, But Not a Guide

Just let me say: there is something perfect about a one-choice-only taverna in winter. No menu. No stress. Katerina says, “Dolmades?” and you say, “Yes please.”

That’s how I learned to love broccoli soup. And amygdalota. And a fish called sagros. And stale bread whipped into a miracle with lime juice, fish roe and olive oil.

I once sat alone with a plate of fish stew with capers and tomatoes, and watched the men tinkering with their boats in a little marina. I was the only customer, and the restauranteur wolf‑whistled a water taxi to take me home.

The Fishing Boat Is the Vibe

Another day, I just sat on my balcony and watched the sea, looking towards the powdered blue hills of the Peloponnese. I watched the fishing boats leaving a triangle of wash as they glided out for their night’s fishing. I sipped my wine, no urgency. No guilt. Just me existing in space and time. Eventually, the port fell silent. So did I. But I thought about those little boats and the fishermen in them for the rest of the evening.

Hydra teaches you how to be. How to stop climbing the hill and just enjoy the view. How to live andante.

Coming Home, Slowly

I left Hydra on a February day. The ferry rocked in the wind, the port slowly receding like a dream. But the pace I learned there came with me.

Back in Australia, I try to walk more slowly. I sit down to eat. I speak to strangers.

Sometimes I watch my video of the fisherman and his wife.

And I say ‘kalimera’ to my husband.

Where to stay in Hydra, Greece

Activities to do in Hydra, Greece

How to Get There – Check your Airplane Tickets Here

How to Get There – Book Your Ferry Tickets Here

Hydra Greece Travel Guide by Shelley Dark

Hydra Greece Travel Guide by Shelley Dark

Hydra Greece Travel Guide by Shelley Dark

Hydra Greece Travel Guide by Shelley Dark

Hydra Greece Travel Guide by Shelley Dark

Hydra Greece Travel Guide by Shelley Dark

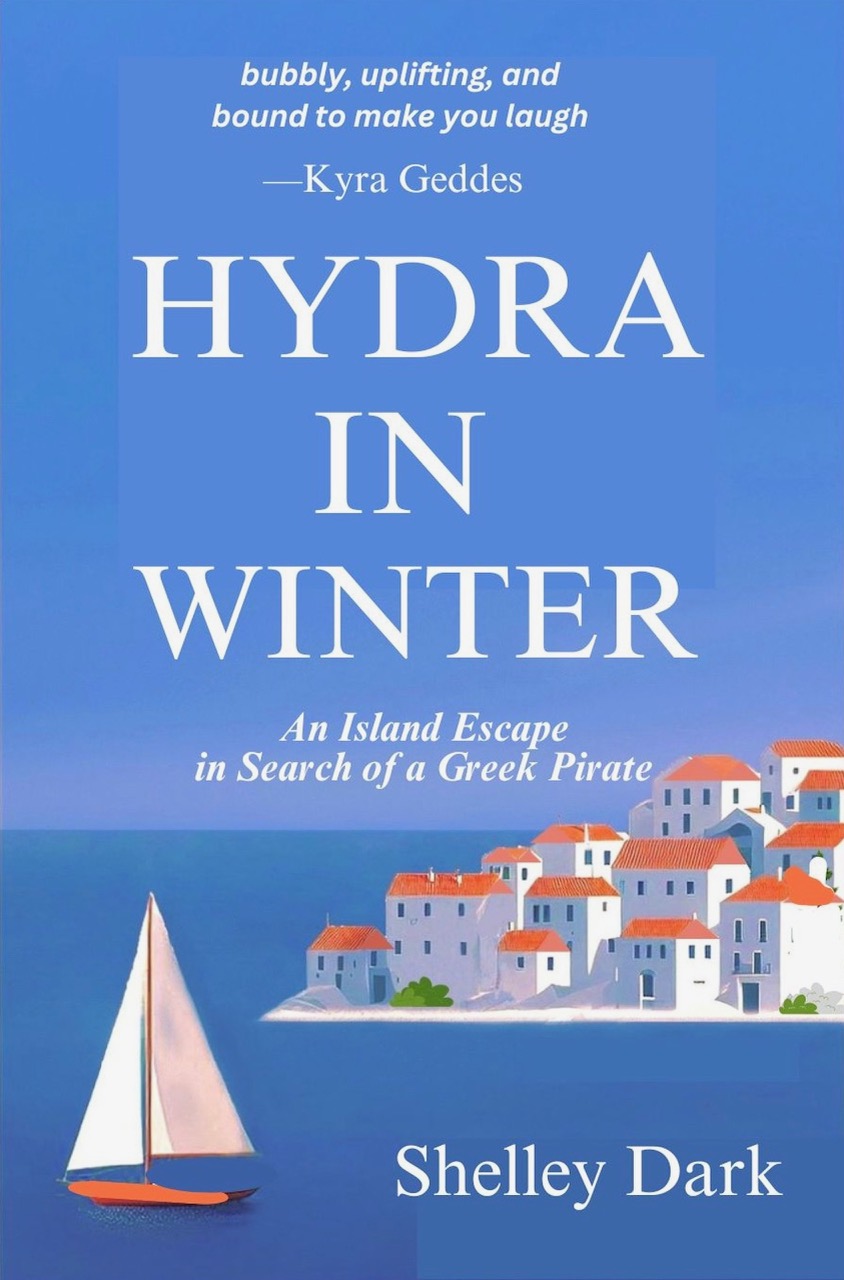

Hydra in Winter_Book by Shelley Dark

Shelley Dark and her husband, John, swapped cattle farming for the beach on Australia’s Sunshine Coast—after a lifetime of mustering, branding, and wrangling both livestock and children. A former teacher (who once taught in a town with 10 people and 15 dogs), Shelley has also been a ringer (cowhand), an average horse rider, a better motorbike rider, and an obsessive gardener and garden designer.

Now she writes obsessively. Her debut travel memoir Hydra in Winter sat for months at #1 on Amazon Australia and was named a Notable Book of 2025 by The Weekend Australian. This November, she launches her historical novel, Son of Hydra, about her husband’s ancestor, a convicted Greek pirate who washed up in colonial New South Wales.

What’s next? The Pirate’s Wife. More memoirs. Or maybe The Cream Bun Lover’s Guide to Australia.

Photos: all photos in this article are kindly provided by Shelley Dark

Connect with Shelley Dark here:

Read more articles here:

Travel & food guide to Sithonia, Halkidiki

Family holidays in Preveza, Greece – What to do

Insider’s Guide – Discover Naxos with Lena Vlastara

Insider’s Guide – Syros for families by Betty Chatzisavvidou

Zagori, Greece – Family-friendly Travel Itinerary

Insider’s guide to Ikaria island, Greece – by Areti Kotsore

Disclaimer: This post contains affiliate links. It’s one of the ways I get paid as a content creator – if you make any purchases using my links, I might earn a commission at no extra cost to you. Thank you for supporting me as a content creator.